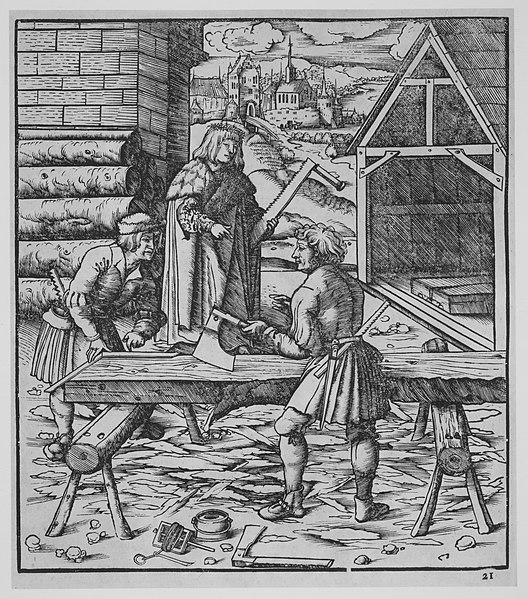

The preparation of wood for construction began with the felling of trees in the forest where the trunks were delimbed and debarked. The tree was preferably harvested in the summertime, when the sap is low, and the cambium layer beneath the bark is fragile. The bark was then more easily removed, an arduous task if the tree is felled in the winter. No material was wasted, and even the smallest branch could be used for laths or ‘wattle’, or for fuel. Fallen timber was seldom prepared in the woods, save perhaps for cutting lengths and ‘rivening’, where the logs we would be split lengthwise using axe, wedge, and maul, which made the transportation of the timber easier, but also allowed for the wood to begin drying faster. Often, the wood was left to season for a year or more. The timber would be transported by road or waterway to a framing site, not necessarily the place of erection. At the framing place, the wood was further riven, squared, ripped, and cut to length using broad axes and saws. The cutting and drilling of different joints were executed and fitted on the ground before the building was raised. Further finishing involved planing, sanding, carving, and paint.

Posts and beams were squared by difficult and dangerous labour, either on the ground on top of dunnage, or on trestles. It involved the use of the felling axe to cut notches, the broad axe to split away the tangent, and the adze and plane to dress the surface. To save labour, some beams were squared and planed on only two opposite sides and were used for hidden work above plaster ceilings, or for barns. The use of the axe and the adze was especially popular in alpine and eastern Europe, where softwoods were stacked horizontally. In the west, post and beam framing required different preparation using saw and chisel. There, improvement in iron work allowed for the development of two-handed saws thin enough to cut but strong enough not to buckle or break. Tension was provided by a frame that tightened the saw blade, or by two men pulling on handles at either end. Wood to be sawn was placed on high sawhorses or above pits, with one sawyer guiding the cut from above while his unfortunate friend operated the saw from below, showered by sawdust. The task of the sawyers was made easier by the work of blacksmiths, who were able to forge steel blades whose teeth were fashioned not only to cut the wood but to remove the fibres with ‘rakers’.

In a 14th century English poem entitled The Debate of the Carpenter’s Tools, we are introduced to a collection of animated medieval carpentry tools who are having an argument as to the merits of their master. Some of the debaters are familiar, such as the “brode ax”, the “squyre”, and the “lyne and chalke”, while other names are more obscure: the “twybylle”, the “wymbylle”, and the “skantyllyon”. At least 26 tools are named.

Then seyd the Whetston,

“Thof my mayster thryft be gone,

I schall hym helpe within this yere

To gete hym twenti merke clere.

Hys axes schall I make full scharpe,

That thei may lyghtly do ther werke.

To make my master a ryche man

I schall asey if that I cane.”

To hym than seyd the Adys,

And seyd, “Ye, syr, God gladys.

To speke of thryfft, it wyll not be,

Ne never I thinke that he schall thé.

For he wyll drynke more on a dey

Than thou cane lyghtly arne in twey;

Therfor thi tonge I rede thou hold

And speke no more no wordys so bold.”

To the Adys than seyd the Fyle,

“Thou schuldys not thi mayster revyle;

For thoff he be unhappy.

Excerpt from The Debate of the Carpenter’s Tools (circa 1340)