The Classical Chinese philosophers would often use carpentry lay-out as a metaphor for correctness and righteousness. In the 3rd century BC, Xunzi remarked:

“When the plumb-line with its ink is truly laid-out, one cannot be deceived as to whether a thing is straight or crooked… When the square and compass are truly applied, one cannot be mistaken as to squareness and roundness. So when once [the honourable man] has investigated rightness of conduct, he cannot be deceived by what is false.”

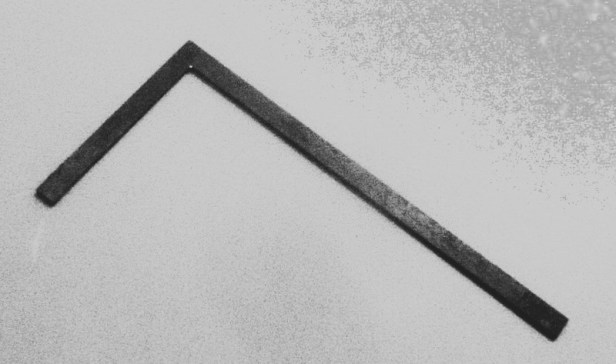

For marking in measuring, the Chinese carpenter employed a bamboo brush and string line marker fed by an ink holder. A length of bamboo would often serve as a storey pole or long rule to lay out larger dimensions horizontally or vertically. The most important ruler, and arguably the most important tool in the kit, was the steel graduated right-angled carpenter’s square. The tongue, or short side of the square, represented the Chinese foot, or chi, divided into 10 inches, or cun. Like the western foot, the Chi may have once had some relation to the human body, but its actual length varied over time, with each dynasty having an “official foot” and the measurement varying from region to region. In fact, the rule could vary from carpenter to carpenter, as squares were often handed down from master to apprentice.

The long side of the square, or blade, was of a length proportional to the short side and was known as the “foot rule” or Zhen Chi. Both the tongue and blade of the carpenter square were marked or coloured with favourable measurements according to the Chinese sense of numerology and proportion. Certain numbers were said to be symbolic of wealth or health.