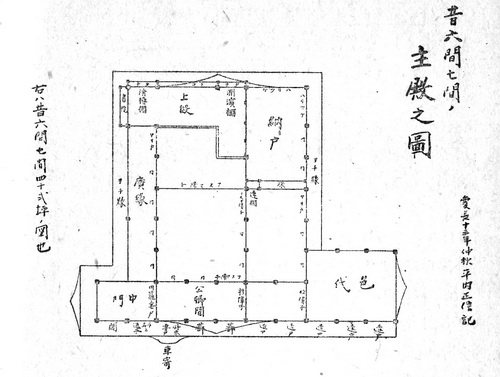

Early on in Japanese feudal society, the growth of urban areas fostered a standardization of residential construction techniques through the proliferation of craft guilds and by the written instructions created by hereditary master carpenters in the service of the aristocracy. Building records were kept on scrolls and included plans, dimensions, procedures, and construction details. These plans relied on uniform measurements and modules such as the shaku (foot), ken (six feet), and the area measurement tsubo (one square ken). Room sizes were usually limited to two ken in width. This modular system was known as tatami-ware; rooms were laid out in proportion to a certain number of straw mats. Standard rectangular grid patterns allowed for efficient installation of ready-made products such the tatami and shoji.

Through standardization, residential house forms had limited variations and professional architects were not required. Carpenters were thus able to concentrate their energy on perfecting technique. House building became simple, cheap, and fast. Buildings were easily repaired and added to. There was no need to question what was seen as a perfect system and this attitude agreed with the Japanese world view that was feudal, Buddhist and Confucian. One did not question the ways of one’s parents, masters, or nature. The shogun dictated the height, size, and placement of houses, neighbourhoods, and towns according to strict rules regarding social status. The Japanese carpentry system was uniform nationally thanks to feudal legislation, written on scrolls and enforced by hereditary officials.

Traditional Japanese carpentry and carpenters may be viewed by outsiders as being stagnated by these official rules, lacking creativity, submissive to technical and social standardization, and overly-influenced by Buddhist and Confucianist humility. However, the ken system, according to Heino Engel, allows for “immense free play within spaces in space”. It is easily adaptable to an infinite number of possible house plans. Furthermore, the simplicity of the wood framing left the Japanese carpenter free to attain a high level of detail and refinement. Engle explains that with standardization “the carpenter achieves exacting technical precision and accomplishes highly qualified work with a minimum of time and material”.