The growth of the furniture and building industries in the ancient near east coincided with the creation of regulated workshops following customs demanded by the temple, the state, and the landowning elite. The urban revolution of the fourth to the third millennia BC was a process of separating crafts from the agricultural, household, or communal industries. The birth of great cities such as Thebes, Tyre, or Jerusalem, was a period of class and state formation. High agricultural production and surplus allowed for social stratification wherein we see the emergence of full-time non-farming specialists such as priests, princes, and craftspeople.

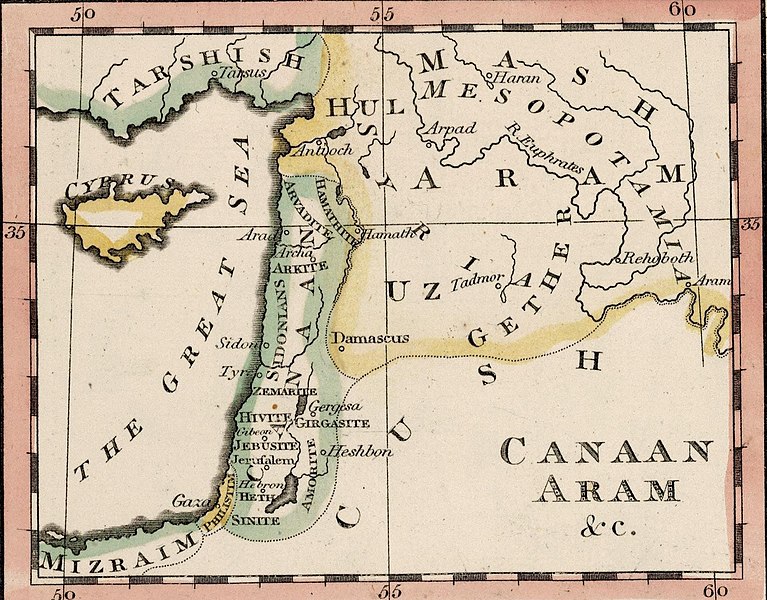

Excavations by Flinders-Petrie at El Lahun showed professional woodworking as a major industry as far back as 2750 BCE, producing a variety of crafts including furniture-making, boatbuilding, house carpentry, and this being Egypt, widespread production of wooden sarcophagi. In Egypt and elsewhere across the ancient Fertile Crescent, craftspeople, both indentured and free, were strictly assigned to their station, through hereditary succession. Carpenters worked mostly in family groups and most lived in close proximity in the town. Rural carpentry was for the most part done by the farmers themselves. Most of the work for the professional carpenter came from long-term contracts with the aristocracy, building houses, palaces, forts, temples, and tombs. At Ugarit, in what is now Syria, special quarters were occupied by imported Egyptian craftsmen. Companies of northern craftspeople frequently travelled to Egypt in search of work. Many workshops and jobsites throughout the region contained a mixture of domestic and foreign workers.

The eastern Mediterranean region, in what is now Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, was caught between the empires of Mesopotamia and Egypt that resulted in a defensive urbanization of the tribal people there. For the Hebrews (one of the hardiest groups), the term harash denoted a professional worker in stone or wood, a craftsman. After the ‘Babylonian Captivity,’ in which generations of Israelite craftspeople were bound in slavery to their Mesopotamian masters, returning artisans organized themselves into guilds called mishpahath, meaning “clans”. Reflecting the familial nature of the industry, the business was passed on from father to son. These proprietors were sometimes assisted by other workers, either free or slave. A master carpenter was known as Yoab or “Father.”