The ideal expression of Japanese residential building is the Sukiya, or ‘teahouse’ style, which came into fashion in the late sixteenth century. Within the humble and natural simplicity of the form, there are strict rules regarding proportion and lay-out. Japanese Sukiya architecture is sophisticated and yet simplistic.

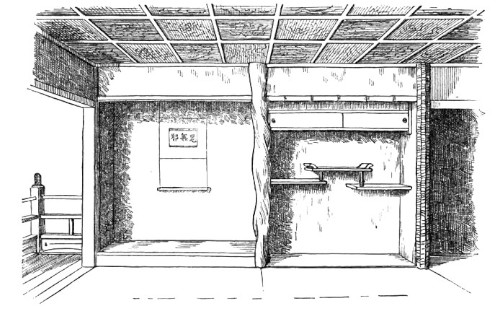

Preference is given to natural and unadorned materials. Nature and the built environments are not opposed to each other but integrated together. Primitive and modern are intermingled and the commonplace is celebrated. As every Japanese is expected to be submissive and selfless in his social relations, so too do all people owe a debt to nature. To build in wood is to join human wisdom with the kami of the trees. Interior decoration is sparse; the beauty of the natural materials is enough. This includes not only the plain exposed wood, but also the woven floor mats, earthen plaster, rice paper screens, and rustic pottery. Furniture is minimal and any pieces are low and small. Rooms are multifunctional and may be made smaller or larger using sliding doors. Storage is provided by ingenious built-in cabinets and shelving.

Zen is a philosophy of humbleness and simplicity. Natural wood elements, with their irregularity and imperfections are a reminder of the frailty of all matter. In the stark semi- darkness of the tearoom, we can find a solitary existence beyond space and time.