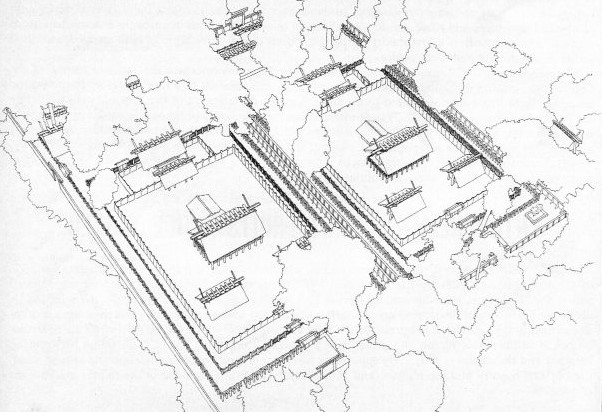

The Imperial Shrine at Ise is typical of all major Shinto temples in Japan, in that it is comprised of a series of fenced enclosures within which are built various pathways, bridges, gateways, and buildings. It is unique in its construction because of its great antiquity, celebrating both the ancient religion but also the indigenous architectural heritage of Japan before the profound influence of Chinese culture and the Buddhist faith, in the 8th century AD. The central shrine dedicated to the Sun Goddess may be hundreds of years older.

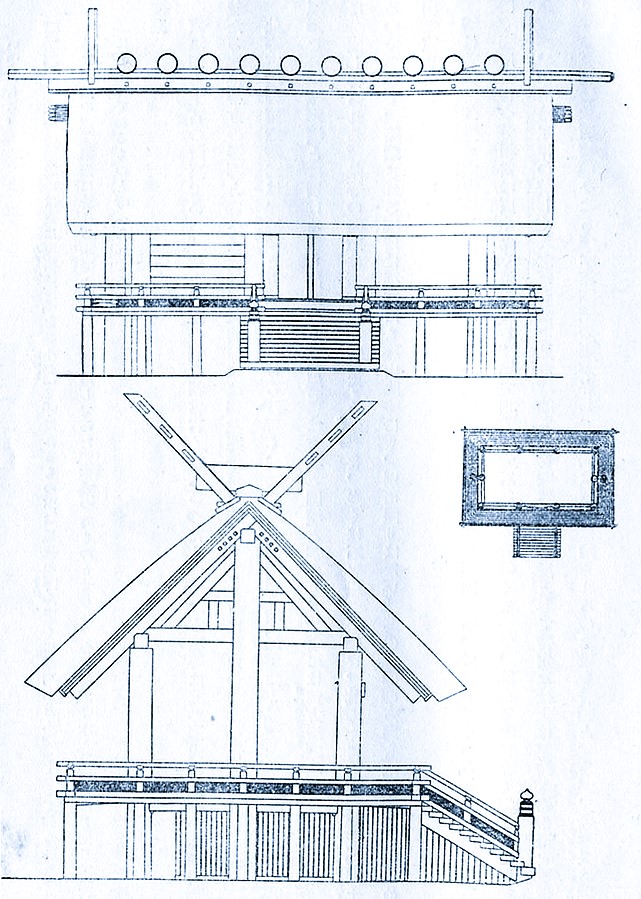

The central shrine itself resembles a rustic granary and is evocative of the Neolithic past when a people named the Yayoi first establish permanent rice agriculture, perhaps influenced by migrants from south-east Asia. Prior to that, early dwellings resembled the conical pit-house found throughout the paleolithic world. Yayoi culture adopted a building technique based on the introduction of a ridgepole at the top of the roof, creating a gabled, rectangular structure with a raised wooden floor carried on piles, or ‘stilts’, sunk in the ground. It is an architectural form that can be found as far away as India and Melanesia. Similar details can be identified throughout southern Asia: curved and “saddle-backed” roofs, cantilevered eaves, verandahs, and decorated gables. The Ise shrine features crossed gable “finials”, suggestive of animal horns. The ‘Sacred Heart Pillar’, Shin no Mihashira, at one end, is a column with no structural purpose, perhaps of totemic origin, a symbolic axis mundi, or ‘world-tree’, connecting the ever-lasting earth and sky with mortal existence. As such the shrine has been associated with imperial divinity and the most sacred relics are deposited within the shrine, where only the Emperor of Japan may enter.

The periodic reconstruction of the Ise shrine, called Shikenen Sengu, involves careful preparation of the white Hinoki cypress, which is felled and then cured for 3 to 10 years. Accidents that cause the slightest bad cut, nick, or dent in the precious wood are considered defilements and the piece is made again. The process is repeated every 20 years and lasts for 17 years, with two identical shrines being renewed on an alternate basis. The tradition rose out of the practical necessity of having to maintain a wooden shrine and has come to symbolize the endless revitalization of nature and its deities.

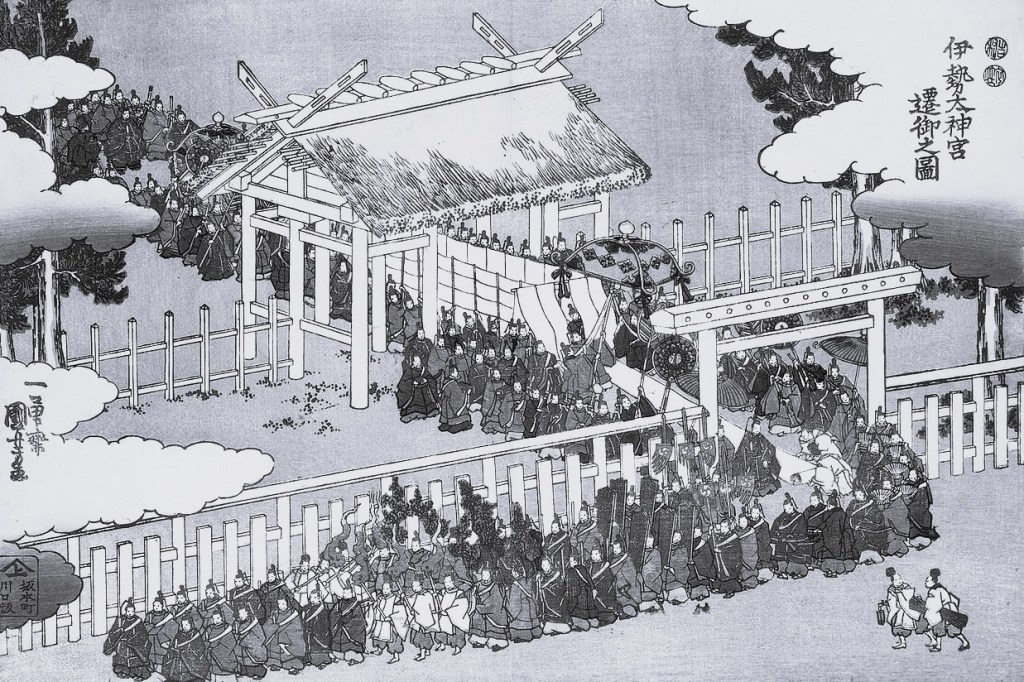

There are at least 30 separate Shinto rituals performed at certain times during the construction process at Ise, re-occuring from every two years to every 65 years. Preparatory rites are performed for those actions that disturb the natural environment, such as tree-harvesting or ground-breaking, where offerings and apologies are given to appease the gods of earth and wood for their sacrifice in service of the great sun goddess Amaterasu. This emphasises the Shinto belief in the interdependence of all living things. Other rituals occur at certain phases of the construction work, where master carpenters assume the role of lay priests. The gods are evoked and asked for protection of the workers and of the sacred wood. Some parts of the shrine have rituals of their own: the placement in the earth of the sacred pillar, the placement of the ridge, and the dedication of the wooden boxes that will contain the ritual objects. Many festivals accompany these rituals, including a public parade through the town that celebrates the delivery of the hinoki for the shrine. Some rituals involve only Shinto priests and temple carpenters, the miyadaiku. Rituals within the inner sanctum are restricted to members of the Japanese imperial family.